FOSS4G Presentations: Multiple Rounds of acceptance

Basic Considerations

There are many considerations that went into the Program Committee’s decisions about which abstracts to accept for this year’s conference, as described previously by FOSS4G ’17 Conference Chair Michael Terner. The most basic one, of course, is that we could only select roughly 250 oral presentations and 50 posters out of the 424 abstracts submitted, due to space and time constraints. But beyond that we wanted a quality program that was comprehensive with respect to the many applications of FOSS4G, and that reflected the diversity of people in our Community: from users to developers, from the renowned to the lesser-known, from business to government to the academy, and from North America to the rest of the world.

The selection process for oral presentations therefore proceeded in multiple rounds, producing 251 acceptances over a five-week period from March 22 to April 28:

- The Program Committee selected its top 13 abstracts for early acceptance;

- The Community voted through an open process on its favorites, resulting in another 47 acceptances;

- The Academic Committee reviewed the 49 abstracts submitted for consideration as academic papers and selected another 30;

- A more methodical ranking of abstracts by the Program Committee generated a middle set of 90 acceptances;

- The Program Committee accepted another 46 that they considered of particular interest and with the additional goal of diversifying content;

- And finally, the Program Committee accepted another 25 abstracts with the main goal of diversifying speakers.

Another 58 abstracts were accepted for posters, 41 are on a waitlist, and 74 were rejected or withdrawn.

What follows is a somewhat idealized description of the process followed by the Program Committee.

Oral Presentations

1. Early Acceptance

As the Committee reviewed the abstracts, everyone noted the presentations that they found to be especially interesting. With members from academia, government, and business, including both developers and end-users, we certainly had a diversity of opinions! Nevertheless, when these top picks were collected there were 13 that showed up three or more times, and they received our first notifications of acceptance. Early acceptance was important so that we could begin showing program content early to prospective attendees while the rest of the deliberations proceeded.

2. Community Voting

Many of the readers of this post probably took part in Community Voting, where anyone could look through the abstracts, anonymously presented, and choose the ones of most interest to them, scoring them as either 1 (interested) or 2 (very interested). The Program Committee looked at the total scores or ranking and accepted the top 47 that weren’t previously accepted early.

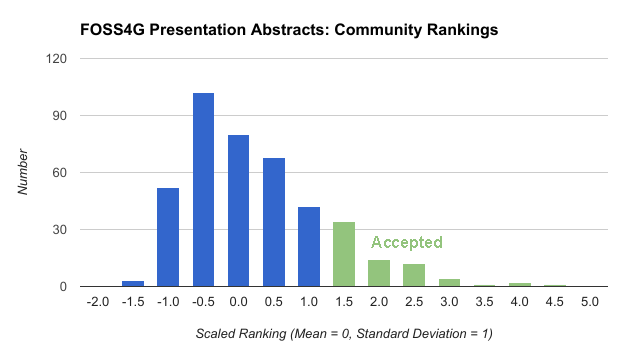

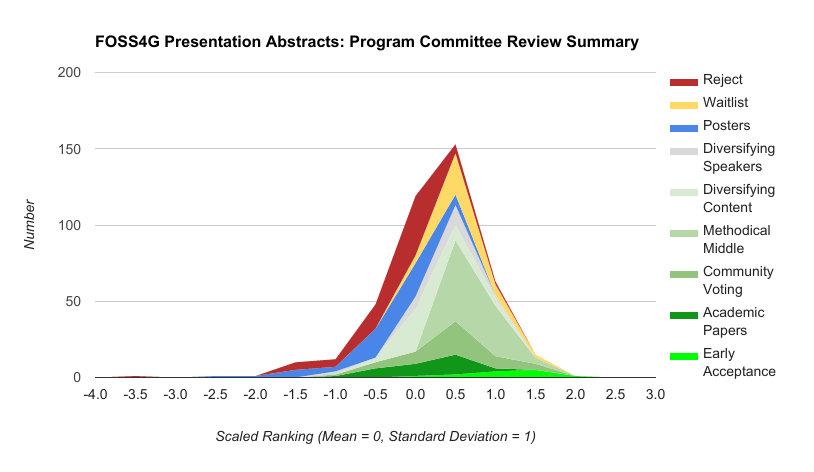

An interesting way of looking at the presentations is to scale their total Community ranking to a Z score = (ranking – mean)/stdDev, which has a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, and plot a histogram:

The accepted presentations had a Z score of 1.08 or higher, in other words they were more than one standard deviation above the mean. The skew to the left indicates a diversity of interest in many talks that received relatively low scores.

3. Academic papers

The Academic Committee had their own selection process that had the additional consideration of whether the abstract would result in a good research paper. As described in a previous blog post, they accepted 30 presentations from the 49 academic abstracts submitted. Because this process occurred in parallel with the Program Committee and Community Voting, which reviewed all submissions, a number of the accepted academic presentations had the option of giving a regular oral presentation instead, and two submitters chose to take that route.

4. Methodical middle

The Program Committee developed a review and scoring system that considered the following characteristics of the abstracts:

Relevance — Does it apply free and open-source tools? Is it geographic in nature?

Credibility — Does the abstract make sense? Is it based on accepted tools and procedures?

Importance — Does it contribute to practice, research, theory, or knowledge? Is it of interest and useful to some portion of the FOSS4G audience? Is it about a common problem or situation that others are likely to have encountered?

Originality — Is this a cutting-edge development? An innovative approach? A new application? An unusual use case?

Practicality — Is the project described a reasonable approach? Is it replicable by others?

Reputation — Is the speaker widely known to the community? Do they have a reputation for quality presentations?

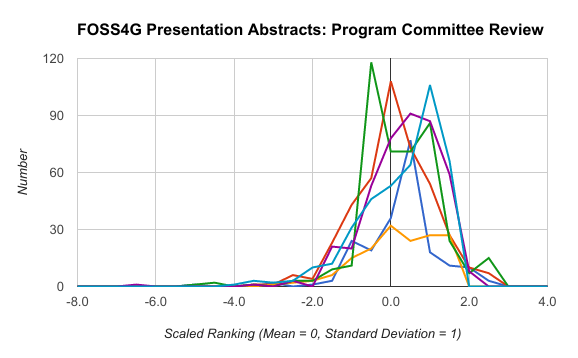

Each reviewer scored the abstracts on these characteristics, as consistently as possible so that their total score could be used to compare one talk with another. But even though there was a common understanding of these characteristics, each reviewer still had their own standards, with some being more generous than others and having higher mean scores. If a Z score is calculated for each reviewer’s set of evaluations, the variation of the distributions is noticeable:

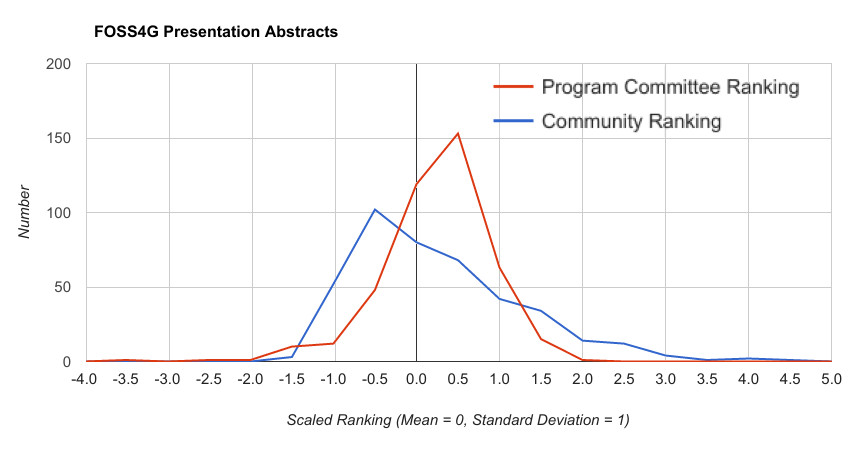

Because the Z scores place the reviewers on a more uniform foundation they can be averaged to produce a useful metric for comparing the presentations. The average Program Committee ranking can then be graphed together with the Community ranking for comparison. The former reveals a more positive skew, probably due to a more inclusive perspective on which topics should be included in the conference.

The Committee agreed to use the average Z score as a ranking metric to choose the middle portion of the presentations, and another 90 received the nod that ranged in Z from 0.1 to 1.3. In order to include as many voices as possible, we excluded from this group additional presentations from previously accepted speakers, as well as some from already-represented organizations that we didn’t feel were distinct enough.

5. Diversifying Content

At this point there were still a number of quality talks that the Program Committee thought were of particular interest, often because they had been flagged by one or two individuals for early acceptance or had been given an overall “accept for oral presentation” status from a majority of reviewers. The Committee also wanted to ensure that some presentations addressed the less represented areas of FOSS4G development and use. At this juncture, we also considered the additional submissions from speakers or organizations that had already had a talk accepted. We agreed that a number of speakers had two strong abstracts worthy of acceptance, and a number of organizations could also contribute more without over-representation. In total, another 46 presentations were accepted.

6. Diversifying Speakers

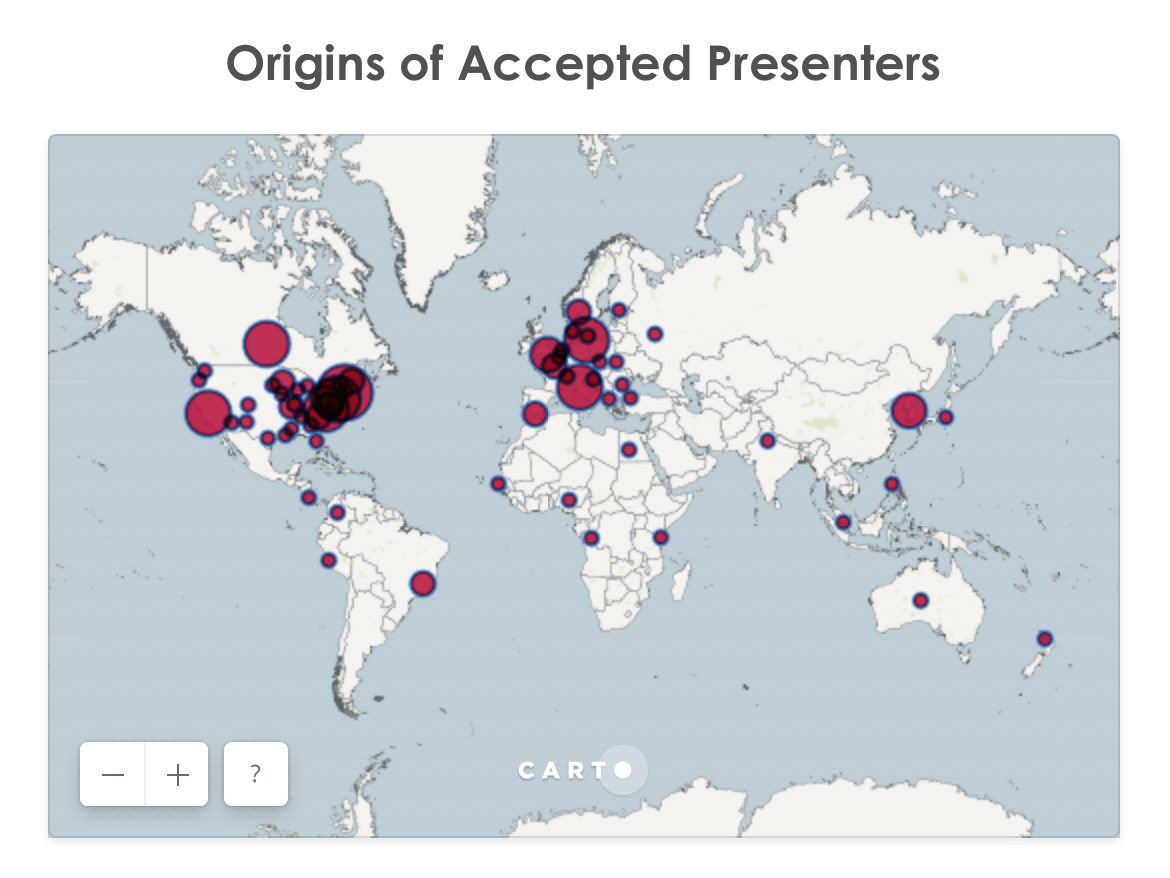

Finally, the Program Committee analyzed the distribution of speakers to ensure there was a diversity of voices. In particular we wanted to make sure that the gender and geographic distribution of accepted presentations were not too far away from the overall ratio of submissions. Gender, as it turned out, was not an issue, with 18% of the accepted abstracts already coming from women, who submitted 14% of the abstracts. Geography was not as simple, however, and we took another look at abstracts from underrepresented regions to see if we missed submissions of interest. This allowed us to increase the accepted presentations to the vicinity of the submitted fraction in every region:

| Region | % Accepted : % Submitted |

|---|---|

| South Asia | 0.4% : 0.2% |

| Middle East and North Africa | 0.8% : 1.2% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1.6% : 1.2% |

| Australia | 1.6% : 1.4% |

| Latin America | 2.8% : 3.1% |

| East Asia | 5.2% : 5.8% |

| Europe | 25.7% : 28.7% |

| North America | 61.8% : 58.3% |

We also checked up on conference sponsors to see if they had at least one accepted presentation, which they all already did. In this final round another 25 presentations were accepted.

The final result, 251 out of 424 abstracts accepted for oral presentations, represents a 59% acceptance rate.

Posters

Abstracts that didn’t make the above cut were then considered for posters, in particular if their topic would lend itself well to a printed presentation. The Academic Committee chose 15 posters, and the Program Committee added another 46. Three of the presenters accepted for academic posters and that were also selected for oral presentations by the Program Committee opted for the latter, resulting in 58 posters or 14% of the total.

Waitlist

A number of the remaining abstracts were put on a waitlist for possible later acceptance, as we refine the number of presentations we can accommodate, the organization of the topic sessions, and allow for some inevitable attrition within the accepted papers. There are 41 submissions in this category, or 10%.

Rejections

Relatively few abstracts were rejected outright. Of these, several were duplicate submissions; a few were uniformly rejected by the Program Committee or the Academic Committee based on scoring criteria; and the remainder were submissions from one speaker or organization that had another talk accepted and weren’t distinctive. There were 73 submissions that were rejected (17%), and one submission that was withdrawn early on in the process.

In Conclusion

The overall process can be visualized in this histogram of the number of presentations of each type according to their scaled ranking (Z score):

As we hope you will agree, the Program Committee took great care to use an even-handed approach that fairly represented the many technologies and people that make up the FOSS4G community. With such a wealth of quality submissions and a limited amount of time and space to present them all, accepting only a fraction was a necessary but difficult task. It was also one that we found to be both interesting and rewarding, and we are very proud of the result. We greatly appreciate the many people who took the time to submit their abstracts.

We invite everyone to Boston in August for an awesome FOSS4G! You can learn more about the accepted presentations here.

(NB: Since finalizing these results, a few of the accepted presentations were withdrawn due to authors not being able to attend, and a few have changed categories, e.g. from oral presentation to poster. Additional changes will undoubtedly be forthcoming. Therefore, the final numbers in the program will differ somewhat from the snapshot presented above.)